ISRA FACTSHEETS

ISRA FACTSHEETS

WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN REGION

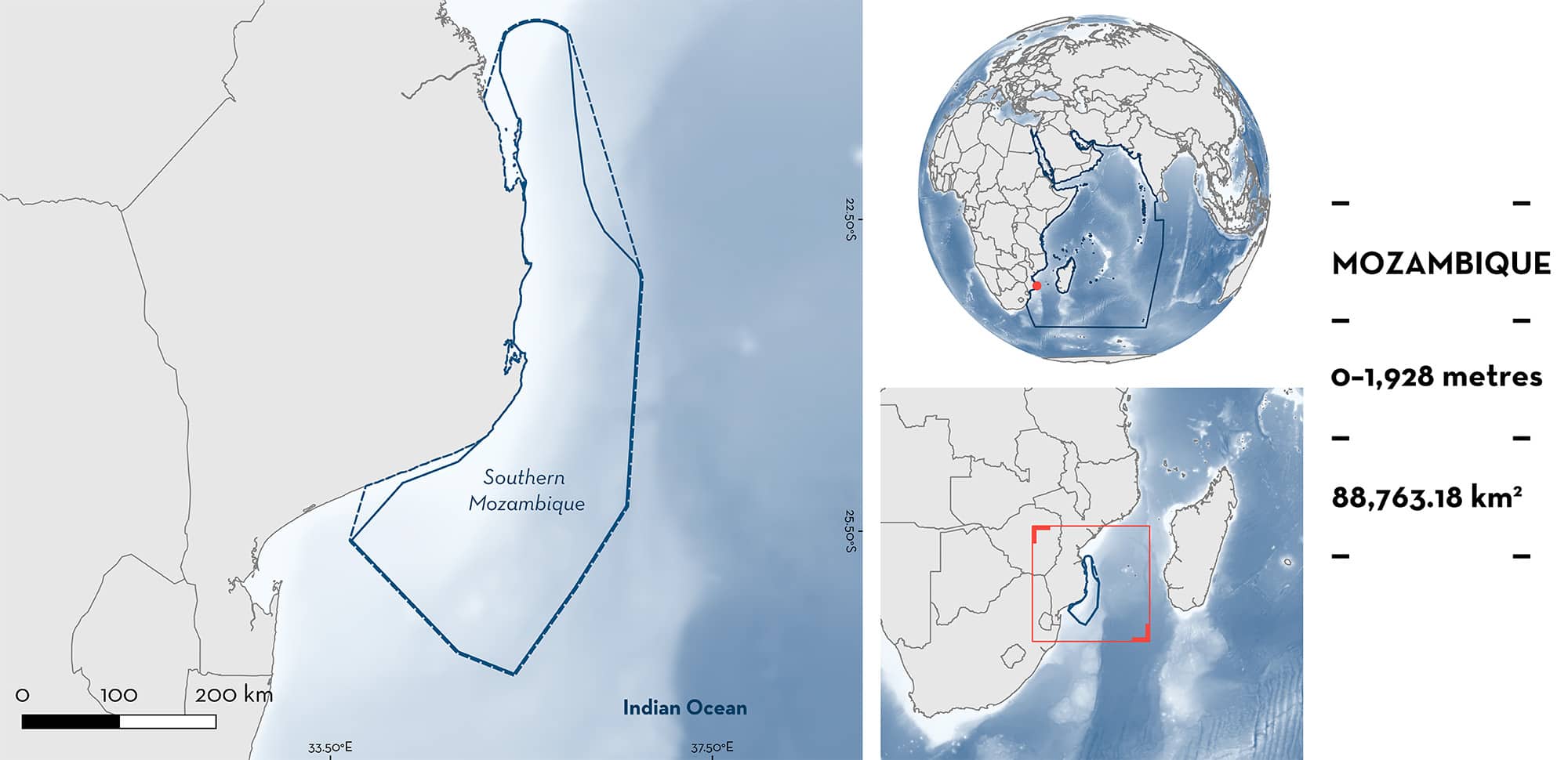

Southern Mozambique

Summary

Southern Mozambique is a coastal and pelagic area in the southwestern Mozambique Channel. This area is in a region characterised by its dynamic oceanography, driven by southwards-flowing mesoscale eddies, the narrow continental shelf, and the wide Delagoa Bight. There are a wide range of habitats in the area, including rocky reefs, coral reefs, extensive areas of sandy substrate, shelf slopes, and pelagic waters. The area overlaps with three Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (Mozambique Channel, Morrumbene to Zavora Bay, Save River to San Sebastian) and the Greater Bazaruto and Tofo Key Biodiversity Areas. Within this area there are: threatened species (e.g., Blacktip Sharks Carcharhinus limbatus) and areas important for movement (e.g., Oceanic Manta Ray Mobula birostris).

Download factsheet

Southern Mozambique

DESCRIPTION OF HABITAT

Southern Mozambique lies in the southwest of the Mozambique Channel. The area includes a large stretch of coastal waters, mostly in the Inhambane Province, and extends offshore into deep and pelagic waters. Along the coast, there are subtropical rocky reefs interspersed on sandy substrates in the south and central sections, and tropical coral and rocky reefs in the northern section, as well as estuaries, mangrove ecosystems, and coastal dunes (Williams et al. 2015; O’Connor & Cullain 2021; Venables et al. 2022). The shelf is narrow and steep in most of the area, but the shelf slope widens considerably in the southern section that lies partly in, and offshore of, the Delagoa Bight. The flow in this area is dominated by mesoscale eddies moving southward along the Mozambican coast (Schouten et al. 2003). These eddies influence the distribution and abundance of animals in the Channel, from zooplankton (Huggett 2014) to top predators (Tew Kai et al. 2010) and may play a particularly important role in the Southern Mozambique area as they interact with the narrow shelf, driving upwelling and increasing productivity (Rohner 2013; Roberts et al. 2014).

The area overlaps with three Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSAs): the Mozambique Channel, Morrumbene to Zavora Bay, and Save River to San Sebastian EBSAs (CBD 2023a, 2023b, 2023c). It also overlaps with the Greater Bazaruto and the Tofo Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) (KBA 2023a, 2023b), and two protected areas – the Bazaruto Archipelago National Park and the Vilanculos Coastal Wildlife Sanctuary.

This Important Shark and Ray Area is benthopelagic and is delineated from inshore and surface waters (0 m) to 1,928 m based on the depth range of Qualifying Species and the bathymetry of the area.

CRITERION A

VULNERABILITY

Six Qualifying Species considered threatened with extinction according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM regularly occur in the area. Threatened sharks comprise one Endangered species and three Vulnerable species; threatened rays comprise one Endangered species and one Vulnerable species (IUCN 2023).

CRITERION C

SUB-CRITERION C4 – MOVEMENT

Southern Mozambique is an important movement area for four shark and three ray species.

Bull Sharks use this movement corridor for short- and long-distance movements. Seven satellite tracked Bull Sharks tagged in South Africa and Ponta do Ouro, Mozambique, moved through the corridor to Bazaruto, and continued into Sofala Province. At least five of these sharks undertook annual movements through the corridor (north-south and south-north) between 2019–2022 (Lubitz et al. 2023; R Daly unpubl. data 2023). Transboundary movements were also recorded on a coastal acoustic receiver array within this area, with 15 tagged individuals moving between the Inhambane Province and South Africa (Daly et al. 2023). Shorter, regional movements were detected with passive acoustic telemetry, with 38 Bull Sharks tracked between 2018–2023 (>260,000 detections; L Müller & R Daly unpubl. data 2023). Most activity was recorded around the Bazaruto Archipelago and San Sebastian, with extensive movement within and between these locations (e.g., 7,000 movements between two stations in San Sebastian; 61 movements between a station in San Sebastian and one in Bazaruto, ~14 km apart). Movements were also recorded between receivers in San Sebastian and Praia do Tofo (~200 km apart) highlighting the use of the movement corridor (L Müller & R Daly unpubl. data 2023).

Blacktip Sharks were tracked with passive acoustic telemetry between 2020–2023 (R Daly unpubl. data 2023). During this time, >58,000 detections were recorded from ten individuals, mostly around Bazaruto and San Sebastian, showing frequent movement within the northern section of the area. Long-distance movements were also recorded between the Bazaruto/San Sebastian and Praia do Tofo regions (n = 8) and five individuals moved between the Bazaruto/San Sebastian region and South Africa, with some making return journeys to and from the area (Daly et al. 2023).

Of 33 White Sharks tagged with SPOT satellite tags in South Africa in 2012–2013, six individuals travelled north to Mozambique where their hotspot of activity was in this area (Kock et al. 2022). Two individuals moved throughout the whole area in coastal waters, from the Delagoa Bight in the south to north of the Bazaruto Archipelago and continued north into Sofala Province; three moved throughout the south of the area in the Delagoa Bight and offshore, with one shark moving north to Pomene and on to Bazaruto. Another individual spent extensive time in the Delagoa Bight and moved up the coast as far as Pomene (Kock et al. 2022). Two tagged sharks went on to cross the Mozambique Channel, swimming to Madagascar. Furthermore, out of three PAT tagged White Sharks from False Bay, South Africa in 2014, one travelled from False Bay to Southern Mozambique and was captured near Chidenguele at the southern end of the area (A Kock unpubl. data 2023).

A combination of satellite telemetry and photo-identification (ID) show that Whale Sharks move extensively throughout the area, often returning over multiple years. Whale Sharks tracked during 2010–2012 with SPOT5 satellite tags (n = 15) moved in a narrow coastal corridor within this area (Rohner et al. 2018). Despite their ability to dive to ~2,000 m, tracked individuals spent most of their time in shallow, coastal waters, in areas of high productivity likely corresponding with areas of high prey density (Rohner et al. 2018). When Whale Sharks swam away from the coast they used a broad vertical habitat, diving into bathypelagic waters (Brunnschweiler et al. 2009). Photo-ID data collected from 2005–2023 recorded 803 individuals in the area (www.sharkbook.ai, July 2023). Individuals were resighted up to 55 times with a mean of 4.1 resightings. Whale Sharks were seen in up to 13 years (mean = 2.1 years), with 387 individuals (48%) seen in multiple years and 10% seen in >5 years, demonstrating a tendency for some individuals to return to the area over multiple years.

Smalleye Stingrays were tracked (n = 11) with passive acoustic telemetry between 2021–2023 (Marine Megafauna Foundation unpubl. data 2023). During this time, ~30,000 detections were recorded, mostly around Bazaruto and San Sebastian. Some Smalleye Stingrays displayed high site fidelity, detected on up to 54 consecutive days in the array. Most detections were recorded during the night (81%), suggesting a pattern of diurnal movement to and from the reefs. Two individuals were tracked with archival satellite tags deployed in Bazaruto in 2021 for 69 and 120 days, respectively (Marine Megafauna Foundation unpubl. data 2023). Both individuals spent time offshore in the northern section. Their dive depths were mainly in the upper 50 m, but also included regular excursions to >100 m (max = ~200 m), further underlining regular movements into offshore areas. One of the two individuals also moved south to Pomene and spent extensive time in the north of the area, off the Save River.

Reef Manta Rays tracked with passive acoustic telemetry (n = 42) between 2010–2014 showed movement within the area (Venables et al. 2020), predominantly between Praia do Tofo/Zavora and Bazaruto/San Sebastian. Reef Manta Rays frequently moved to, and away from, cleaning stations, spending time within the area without moving further afield in the short periods between detections at cleaning station sites. Movements are likely to connect cleaning stations to potential feeding areas located outside of the acoustic array. This is supported by the diurnal trend in detections: cleaning stations had a clear peak during the day, while a receiver at a feeding site recorded most detections at night (Venables et al. 2020). Of three Reef Manta Rays tracked with satellite tags, two individuals moved north from Bazaruto to areas offshore of the Save River. The third individual moved through the whole area and beyond to South Africa (Marine Megafauna Foundation unpubl. data 2023).

Oceanic Manta Rays tagged with archival satellite tags (n = 7), in 2009, 2011, 2012, and 2023 off Bazaruto and Praia do Tofo moved extensively throughout this area (mean track length = 53 days, range = 22–80 days; Marine Megafauna Foundation unpubl. data 2023). Two individuals moved beyond the area into South Africa. Oceanic Manta Rays occupied offshore waters and all individuals moved between Praia do Tofo and Zavora, and in and offshore of the Delagoa Bight. Three individuals used the waters around Pomene in the central section of the area. It is possible that mesoscale eddies in the Mozambique Channel influenced the movements of this species, as most tagged individuals spent the majority of their time off the shelf (Marine Megafauna Foundation unpubl. data 2023).

Download factsheet

SUBMIT A REQUEST

ISRA SPATIAL LAYER REQUEST

To make a request to download the ISRA Layer in either a GIS compatible Shapefile (.shp) or Google Earth compatible Keyhole Markup Language Zipped file (.kmz) please complete the following form. We will review your request and send the download details to you. We will endeavor to send you the requested files as soon as we can. However, please note that this is not an automated process, and before requests are responded to, they undergo internal review and authorization. As such, requests normally take 5–10 working days to process.

Should you have questions about the data or process, please do not hesitate to contact us.