ISRA FACTSHEETS

ISRA FACTSHEETS

WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN REGION

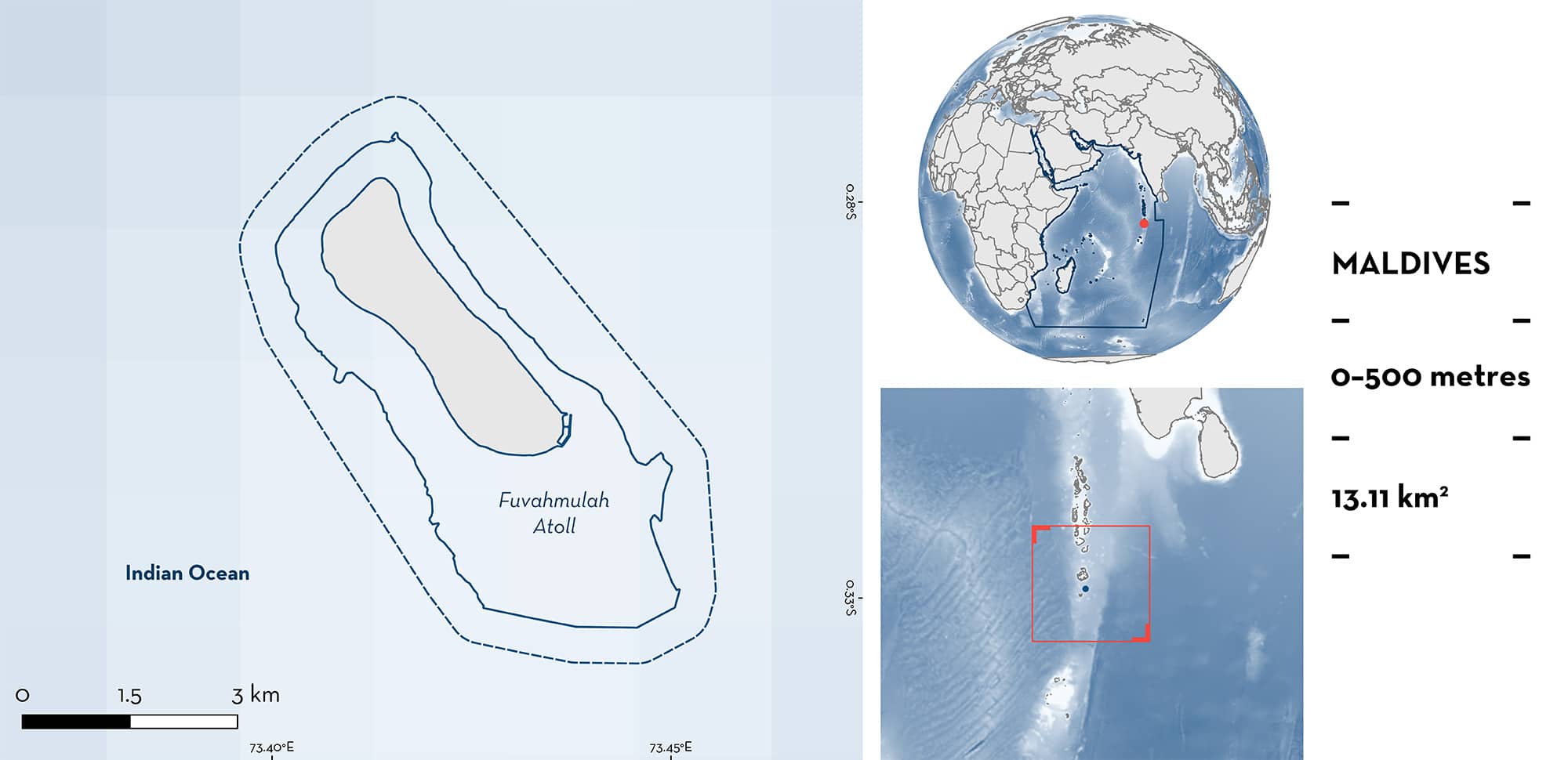

Fuvahmulah Atoll

Summary

Fuvahmulah Atoll is an offshore island in the southern Maldives. Fuvamulah Island, the only island of the atoll, is an oceanic platform reef without a lagoon surrounded by a fringing reef. On the southeastern edge of the area, there is a spur reef, known as Farikede, that extends 2 km from the shore as a gentle sloping coral reef from 0–20 m with a drop off around the side. The area overlaps with Thoondi Area-Fuvahmulah and Farikede Marine Protected Areas and Fuvahmulah UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. Within this area there are: threatened species (e.g., Silvertip Shark Carcharhinus albimarginatus); reproductive areas (e.g., Tiger Shark Galeocerdo cuvier); resting areas (Whitetip Reef Shark Triaenodon obesus); undefined aggregations (e.g., Oceanic Manta Ray Mobula birostris); and distinctive attributes (Pelagic Thresher Alopias pelagicus).

Download factsheet

Fuvahmulah Atoll

DESCRIPTION OF HABITAT

Fuvahmulah Atoll is a small atoll located in the southern Maldives Archipelago, sitting centrally upon the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge. The area is composed of Fuvamulah Island which is an oceanic platform reef without a lagoon (Stevens & Froman 2019). Fuvahmulah Atoll, also known as Gnaviyani Atoll, is located on the equatorial channel between Huvadhoo Atoll to the north and Addu Atoll to the south (David & Schlurmann 2020).

Fuvahmulah Island is surrounded by a fringing reef (David & Schlurmann 2020). The area is characterised by a shallow sloping coral reef from 0–10 m depth extending to a steep reef drop-off to depths of 500 m. On the southeastern edge of the area, there is a spur reef, known as Farikede, that extends 2 km from the shore. The top of the Farikede reef is characterised by a gentle sloping coral reef from 0–20 m with a drop-off around the side. Around the southeast of the island there is a flat plateau 40–50 m deep known as Kedeyre. The northeast fringing reef is known as Thoondi.

The weather in the Maldives is strongly influenced by the South Asian monsoon, especially the northern and central atolls as these are closer to the Indian subcontinent (Anderson et al. 2011). Two monsoons annually occur in Maldives with the southwest monsoon (locally known as Hulhan’gu) from May to November, and the northeast monsoon (locally known as Iruvai) from January to March (Shankar et al. 2002; Anderson et al. 2011). The monsoonal winds generate oceanic currents mirroring the direction and intensity of the winds that, together with the South Equatorial Current, interact with the geomorphology of the Maldivian archipelago generating upwellings through Island Mass Effect (Su et al. 2021). The monsoons result in high waves which peak in July (David et al. 2019). Tidal currents and ocean circulation velocities associated with tides are considerably lower than those induced by waves (David & Schlurmann 2020).

This area overlaps with Thoondi Area-Fuvahmulah Marine Protected Area and Farikede Marine Protected Area. The area also overlaps with the Fuvahmulah UNESCO Biosphere Reserve (UNESCO 2020).

This Important Shark and Ray Area is benthopelagic and is delineated from inshore and surface waters (0 m) to 500 m based on the bathymetry of the area.

CRITERION A

VULNERABILITY

Six Qualifying Species considered threatened with extinction according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM regularly occur in the area. Threatened sharks comprise one Critically Endangered species, two Endangered species, and two Vulnerable species; threatened rays comprise one Endangered species (IUCN 2023).

CRITERION C

SUB-CRITERION C1 – REPRODUCTIVE AREAS

Fuvahmulah Atoll is an important reproductive area for two shark species.

Photo-identification and visual observations of abdominal distensions in Tiger Sharks were regularly collected between 2016–2023 during scuba diving (Vossgaetter 2023). A total of 236 Tiger Sharks have been identified in the area. The large majority of sharks are female (84%, n = 199), with an average size of 320 cm total length (TL) (SD = 50 cm, n = 213; visual size estimates confirmed through laser photogrammetry). A total of 99 females (which represent 57% of the females assessed as juvenile/adult), were resighted over the study period displaying strong inter-annual site fidelity. Visual confirmation of abdominal distensions over extended time periods (1–5 months) suggests that they gestate in the area, with periods of absence for apparent parturition (since animals returned with no abdominal distension). A third of the adult females (n = 33) displayed at least one complete reproductive cycle. Modelled residency using maximum likelihood methods suggests adult female Tiger Sharks spent 62.9 ± 8.7 (SE) days in Fuvahmulah, with a substantially larger aggregation size and longer residence period than juvenile females (L Vossgaetter unpubl. data 2023). Additionally, Remote Underwater Camera (RUC) data collected over 63 days between March and August 2022 recorded six pregnant females (determined pregnant by the presence of distended abdomens; K Zerr et al. unpubl. data 2023). This is the only known aggregation of Tiger Sharks in the Maldives.

Whitetip Reef Sharks are abundant species in the area and were recorded on 44 of 226 snorkel and dive Underwater Visual Surveys (UVS) by the Manta Trust over 86 days in March and April 2021–2023 with the maximum number of individuals sighted being eight (S Hilbourne unpubl. data 2023). RUC deployments conducted in March-August 2022 recorded Whitetip Reef Sharks on 89% of deployment days (n = 63) and at all three of the forereef deployment sites making this species the most commonly occurring throughout the study (K Zerr et al. unpubl. data 2023). Young-of-the-year (YOY) and juvenile Whitetip Reef Sharks aggregate in the area. Aggregations of up to six juveniles have been documented regularly in overhanging ledges on the reef. Local Ecological Knowledge (LEK) indicates that these aggregations are year-round and have been documented since 2016 (Fuvahmulah Dive School pers. obs. 2023). Individuals in the aggregations have an estimated size of 60–70 cm TL (close to the reported size-at-birth of 30–52 cm TL; Ebert et al. 2021). Additionally, there are several reports of Whitetip Reef Sharks mating in April 2023 (S Hilbourne pers. obs. 2023) and in previous years (Fuvahmulah Dive School pers. obs. 2023).

CRITERION C

SUB-CRITERION C3 – RESTING AREAS

Fuvahmulah Atoll is an important resting area for one shark species.

Up to 10 Whitetip Reef Sharks can be observed during dives, resting on small sandy patches between coral bommies in the few flat sections of plateau reef, as well as at the deeper section of the plateau (40–55 m), adjacent to the reef slope (Pelagic Divers Fuvahmulah & Fuvahmulah Dive School pers. obs. 2023). Due to the bathymetry of this area, there are limited suitable locations for this species to rest, therefore they aggregate in the few flat sandy areas. LEK indicates Whitetip Reef Sharks can be seen resting on the flats year-round (Pelagic Divers Fuvahmulah & Fuvahmulah Dive School pers. obs. 2023) even though consistent sightings throughout the year are challenging due to the oceanic conditions present at the dive site.

CRITERION C

SUB-CRITERION C5 – UNDEFINED AGGREGATIONS

Fuvahmulah Atoll is an important area for undefined aggregations for three shark and one ray species.

Silvertip Shark aggregations regularly occur in the area. Underwater Visual Census (UVC) during a one-year period (May 2021 to April 2022) documented a total of 104 sightings of Silvertip Sharks with a maximum of 10 sightings during one dive (L Vossgaetter unpubl. data 2023). Based on the records of Fuvahmulah Dive School and Pelagic Divers Fuvahmulah since 2017, Silvertip Sharks used to be more abundant prior to 2020 with dive guides recording >40 individuals during single dives. These large aggregations were recorded in January, March, and June 2017; February 2018; July and September 2019; and January to March 2020 at Farikede (Fuvahmulah Dive School pers. obs. 2023). RUC deployments conducted in March-August 2022 recorded Silvertip Sharks on 16% of deployment days (n = 63) at the southernmost forereef site (Farikede) only (K Zerr et al. unpubl. data 2023). Of those days, the maximum number observed at one time (MaxN) of two or more individuals was recorded in 50% of days indicating frequent observations of >1 individual. Where sightings occurred, the average MaxN per day across the study period was 2.4 and the highest MaxN was six (K Zerr et al. unpubl. data 2023).

Grey Reef Sharks were recorded on 42 of 226 snorkel and dive UVC over 86 days in March and April 2021–2023 with aggregations up to 20 individuals sighted (S Hilbourne unpubl. data 2023). RUC deployments conducted on 63 days in March-August 2022 recorded Grey Reef Sharks on 78% of deployment days and at all three of the forereef deployment sites (K Zerr et al. unpubl. data 2023). Where Grey Reef Sharks were present, 43% of days recorded MaxN values of 2 or more. In 14 days during the study, a MaxN value of 5 or more was recorded. In seven days of the study, a MaxN value of 10 or more was recorded. The largest and most frequent aggregations were recorded at the southernmost site (Farikede) with an overall MaxN of 21 individuals. Where sightings occurred, the average MaxN per day across the study period was 3.98 (K Zerr et al. unpubl. data 2023). Grey Reef Sharks have been observed hunting on the large aggregations of Cottonmouth Jack Uraspis secunda year-round, especially during periods of strong northeast current in groups of up to 20–30 individuals (J Crouch & F Bocchi pers. obs. 2016–2023), suggesting that the aggregation could be linked to feeding, but the main driver of this aggregation remains unknown.

RUC and LEK have documented large schools of up to 30–60 Scalloped Hammerheads. Such large aggregations have been documented opportunistically by divers every year since 2016 (Fuvahmulah Dive School pers. obs. 2023). Aggregations appear to be seasonal with most sightings between February–May and October–December. RUC deployments conducted in March–August 2022 recorded Scalloped Hammerheads on 32% of deployment days (n = 63) and all at three of the forereef deployment sites (K Zerr et al. unpubl. data 2023). Of those days, a MaxN of 2 or more were recorded in 14% of days (n = 3). Overall, the highest MaxN recorded during the study was 7. These aggregations are relevant at the national level since it is one of the last known Scalloped Hammerhead Shark aggregations in the Maldives.

Photo-identification data from 2007–2023 identified 778 different Oceanic Manta Rays from 837 sightings (S Hilbourne unpubl. data 2023). Aggregations in the area are seasonal with a peak between March and May, when sightings go from virtually zero to 60–300 sightings in a 2–4 week period (maximum = 330 sightings over four weeks in 2019). Inter-annual re-sightings have been recorded for 1.5% (n = 11) individuals recorded around Fuvahmulah with the period between seasons ranging 1–8 years (S Hilbourne unpubl. data 2023). Within seasons, residency around this area appears to be limited to a day or two suggesting that this population is transient and moving on to other areas. Behaviour documented during sightings include cleaning (n = 5), courtship behaviour (n = 31), and feeding activity (n = 11) but for the remaining 95% of sightings, the individuals were recorded as ‘just cruising/swimming’ (S Hilbourne unpubl. data 2023). The driver for visitation to Fuvahmulah Atoll by Oceanic Manta Rays is still not understood, but their regular and reliable seasonality makes it an important location of this species. This area represents 86% of the sightings of Oceanic Manta Rays in the Maldives (S Hilbourne unpubl. data 2023).

CRITERION D

SUB-CRITERION D1 – DISTINCTIVENESS

Within Fuvahmulah Atoll, one shark species shows distinct attributes.

Underwater Visual Surveys (UVS), RUC, and LEK over the last 7 years has shown that Pelagic Threshers visit distinct cleaning stations in deeper water at depths of 40–88 m (Fuvahmulah Dive School pers. obs. 2023; F Bocchi unpubl. data 2023; A Nasheed pers. obs. 2017–2023; A Askin, H Hussain & A Mohamed unpubl. data 2023). Based on scuba diving observations, between 2017–2023, individuals can be observed year-round (although mainly seasonally between September–March) visiting cleaning stations individually or in groups of up to three individuals (Fuvahmulah Dive School pers. obs. 2023). RUC deployments conducted from March–August 2022 at a known Pelagic Thresher cleaning station recorded species occurrence in 90% of deployment days (K Zerr et al. unpubl. data 2023). At this site, a daily MaxN of 2–3 was recorded on 63% of days. Posing behaviour, also known as ‘Circular-Stance-Swimming’, wherein Pelagic Threshers initiate cleaning from cleaner fish species through circular swimming, was frequently observed in the images processed (Oliver et al. 2011; K Zerr et al. unpubl. data 2023). Additionally, during close passes of Pelagic Threshers, divers and RUC images have captured images of cleaner fish actively cleaning individual sharks (K Zerr et al. unpubl. data 2023). This is the only known Pelagic Thresher cleaning station in the Western Indian Ocean.

Download factsheet

SUBMIT A REQUEST

ISRA SPATIAL LAYER REQUEST

To make a request to download the ISRA Layer in either a GIS compatible Shapefile (.shp) or Google Earth compatible Keyhole Markup Language Zipped file (.kmz) please complete the following form. We will review your request and send the download details to you. We will endeavor to send you the requested files as soon as we can. However, please note that this is not an automated process, and before requests are responded to, they undergo internal review and authorization. As such, requests normally take 5–10 working days to process.

Should you have questions about the data or process, please do not hesitate to contact us.