ISRA FACTSHEETS

ISRA FACTSHEETS

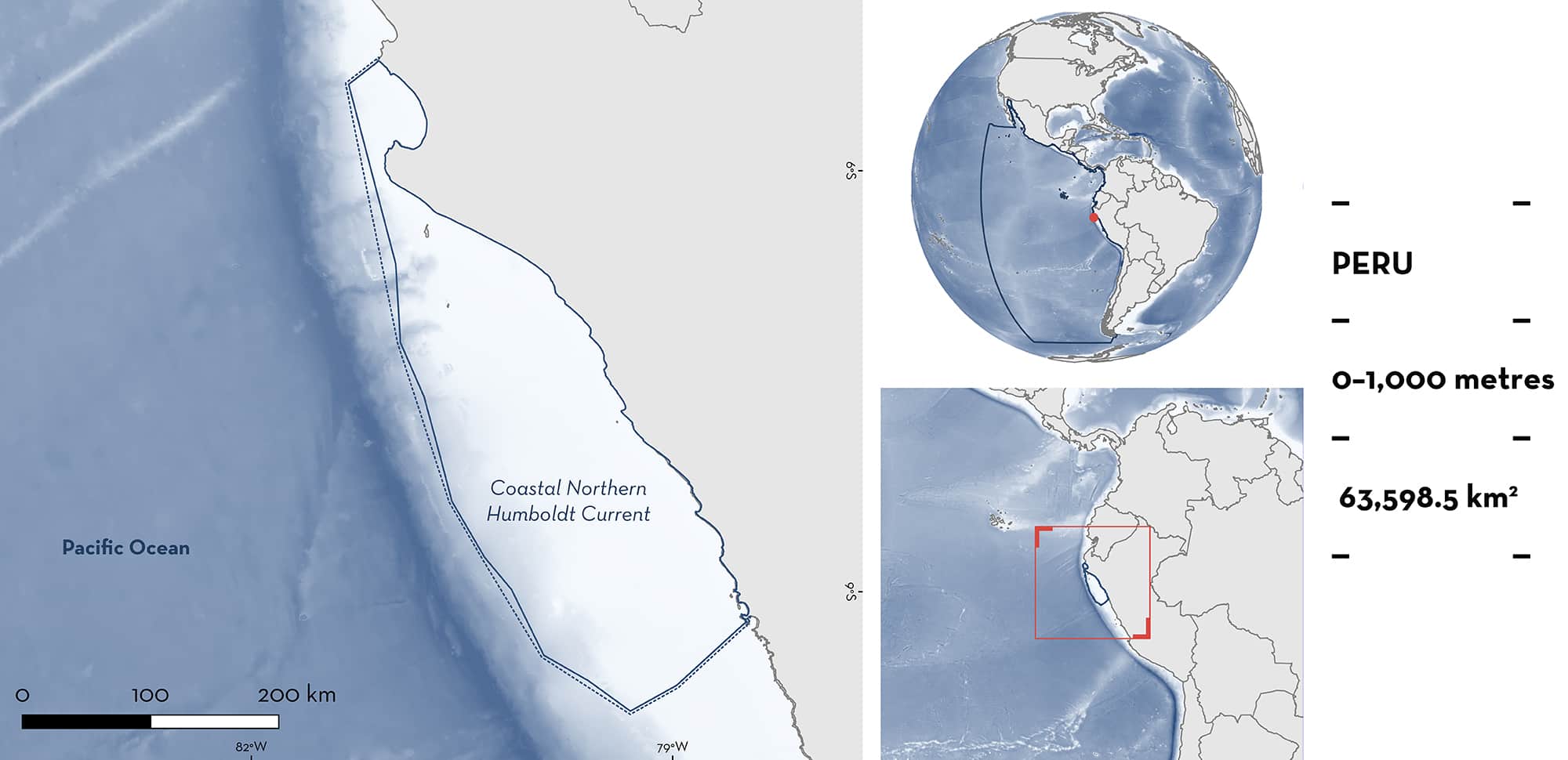

CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICAN PACIFIC REGION

Coastal Northern Humboldt Current

Summary

Coastal Northern Humboldt Current extends from the southern Piura region to northern La Libertad region in Peru. It is located within the Northern Humboldt Current System, one of the most productive marine systems in the world and overlaps with major upwelling centres. The area overlaps with Lobos de Tierra and Lobos de Afuera islands, a marine protected area system which are both Key Biodiversity Areas. The area has exceptional marine productivity and a variety of habitats dominated by rocky shores and sandy substrates. Within this area there are: threatened species (e.g., Spotted Houndshark Triakis maculata); range-restricted species (e.g., Humpback Smoothhound Mustelus whitneyi); reproductive areas (e.g., Smooth Hammerhead Sphyrna zygaena); feeding areas (e.g., Chilean Eagle Ray Myliobatis chilensis); and the area sustains a high diversity of sharks (17 species).

Download factsheet

Coastal Northern Humboldt Current

DESCRIPTION OF HABITAT

Coastal Northern Humboldt Current extends from the southern Piura region to northern La Libertad region in Peru. Situated within the Humboldt Current Large Marine Ecosystem (LME), the area overlaps with the Northern Humboldt Current System (NHCS), which is one of the most productive ocean ecosystems due to its coastal upwelling producing a high abundance of zooplankton that sustains the ecosystem (Pennington et al. 2006). Oceanographic features, associated with wind forcing, create strong upwelling and high levels of primary productivity in the offshore waters of northern Peru (Bakun & Weeks 2008; Montecino & Lange 2009). Warm subtropical waters move closer to the coast in the austral summer and autumn, and coastal upwelling disperses them in winter and spring (Bakun & Weeks 2008). This upwelling, and its associated productivity, allow the development of an exceptionally high biomass of ecologically important marine species such as Peruvian Anchoveta Engraulis ringens and Humboldt Squid Dosidicus gigas (Bakun & Weeks 2008; Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2022).

Within the NHCS, six major upwelling centres have been identified which are characterised by a higher concentration of phytoplankton. These have been classified as Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSA), namely the Humboldt Current Upwelling System in Peru and the Major Upwelling Centers and Seabird Associated with the NHCS (CBD 2020). These centres tend to be associated with prominent continental features such as peninsulas and semi-protected bays where nutrients are concentrated, producing ‘upwelling shadows’ (Graham et al. 1992).

This area overlaps with Punta Illescas which represents the northern most upwelling centre. Punta Illescas has unique coastal topography as the second westernmost point of the south-eastern Pacific shoreline and produces a strong upwelling (Chavez & Messie 2009). It is also at the narrowest part of the continental shelf along the Peruvian coast which enhances productivity (Jacox & Edwards 2011). The northern area is influenced by the Cromwell Current which is the main contributor to coastal upwelling in northern Peru (Zuta & Guillen 1970), allowing a rich demersal subsystem due to its high oxygen levels (Vargas & Mendo 2010), supporting the Peruvian Hake Merluccius gayi peruanus demersal fishery.

This area overlaps with Lobos de Tierra and Lobos de Afuera islands which are part of a marine protected area system and have been identified as Key Biodiversity Areas.

This Important Shark and Ray Area is delineated from surface waters (0 m) to 1,000 m based on the vertical distribution of Qualifying Species that is restricted by the depth contour of this area.

CRITERION A

VULNERABILITY

Sixteen Qualifying Species considered threatened with extinction according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM regularly occur in the area. Threatened sharks comprise four Critically Endangered, two Endangered, and four Vulnerable species. Threatened rays comprise one Endangered, and five Vulnerable species (IUCN 2022).

CRITERION B

RANGE RESTRICTED

Coastal Northern Humboldt Current holds the regular presence of six resident range-restricted species: Chilean Angelshark, Humpback Smoothhound, Spotted Houndshark, Chilean Eagle Ray, Peruvian Eagle Ray, and Shorttail Fanskate. Chilean Angelshark, Spotted Houndshark, Chilean Eagle Ray, and Peruvian Eagle Ray are restricted to the Humboldt Current LME. Shorttail Fanskate occurs primarily in the Humboldt Current LME and only marginally into the Pacific Central-American Coastal LME. Humpback Smoothhound occurs in the Humboldt Current LME and the Pacific Central-American Coastal LME.

These species are regularly encountered and often targeted in small-scale fisheries (Alfaro-Shigueto et al. 2010; Céspedes 2014; Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2016, in press; Córdova-Zavaleta 2022). Some of them represent the most landed sharks (Chilean Angelshark, Humpback Smoothhound) or rays (Chilean Eagle Ray, Peruvian Eagle Ray) in Peru and have their most important landing sites and fishery areas in this area (Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2016, in press; IMARPE landings statistics between 2010–2020). Shorttail Fanskate is the most abundant (according to biomass) bycatch ray species in the Peruvian Hake industrial trawling fishery which operates within this area (Céspedes 2014).

CRITERION C

SUB-CRITERION C1 – REPRODUCTIVE AREAS

Coastal Northern Humboldt Current is an important reproductive area for five sharks.

The Peruvian fishery for Smooth Hammerhead that operates in this area is composed of neonates, young-of-the-year, juveniles, and adult females (Castañeda 2001; Gonzalez-Pestana 2014, 2018; Torres 2018; Córdova-Zavaleta 2022). Studies with samples from ~12,000 individuals indicate that the smallest individuals measured 44 cm of total length (TL) while the size ranged between 70 to 115 cm TL. Size-at-birth for this species is reported at 49–63 cm TL (Rigby et al. 2019). During late austral spring and early summer (November to January) females in advanced pregnancy stages were captured as this life-stage is targeted (Castañeda 2001; Gonzalez-Pestana 2014, 2018). Sharks are born in late spring and early summer (with open umbilical scars recorded), and they stay in this area for their first year with some individuals staying up to two years (Gonzalez-Pestana 2014, 2018).

Tope Shark is caught by small-scale fisheries operating in this area. San Jose and Santa Rosa (Lambayeque region) are the most important landing sites for this species along the Peruvian coast, representing 78% of the total landings of the species in Peru (IMARPE national reports). Between 2015–2019, 382 individuals were sampled within this area. In San Jose (Lambayeque region), animals measured on average 112.5 ± 29 cm TL with a minimum size of 50 cm TL, and in Salaverry (La Libertad region) an average 132.1 ± 23.2 cm TL with a minimum size of 80 cm TL (Córdova-Zavaleta 2022). Most individuals were juveniles (size-at-maturity: 206–235 [males] and 227–244 [females] cm TL; Ebert et al. 2021), and some were young-of-the-year since size-at-birth is between 26–40 cm TL.

Between 2015–2019, 954 Copper Sharks were sampled measuring 105.6 ± 22.3 cm TL with a minimum size of 50 cm TL (Córdova-Zavaleta 2022). Most individuals were juveniles (size-at-maturity: 120–135 [males] and 134–140 [females] cm TL; Peres & Vooren 1991), and some were neonates and young-of-the-year since size-at-birth is between 59–70 cm TL (Ebert et al. 2021; Drew et al. 2017).

Pregnant females of Humpback Smoothhound have been observed in this area. Sampled individuals (n = 41) from March to July 2013, and May to September 2016, were pregnant females (average body size: 88.1 ± 17.8 cm TL) in varied stages of embryonic development. Neonates (n = 16) were also recorded (Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2019). The largest embryo measured 23 cm TL and the smallest free-living neonate, with an open umbilical scar, measured 22.4 cm TL. Additionally, captures of gravid females have been observed during two fishery trips off northern Lambayeque coast and off Punta Illescas (Adriana Gonzalez-Pestana pers. obs. 2022).

Eighty to 85% of Chilean Eagle Ray landings within this area were composed of immature individuals, including neonates (with minimum body sizes of 30 cm disc width [DW]), with mature adult females (some pregnant with litter sizes of 2–4 pups commonly captured in the austral summer; Torres 1978; Castañeda 1994). Between 2015 and 2019, 4,577 individuals were sampled measuring on average 75.6 ± 28.7 cm DW with minimum sizes of 20 cm DW (Córdova-Zavaleta 2022). For this species, the size-at-maturity is 115 cm DW (Castañeda 1994). The size-at-birth is unknown; yet embryos with a body size of 29 cm DW have been reported in this area (Castañeda 1994). Thus, mostly juveniles, including neonates, are recorded in this area.

CRITERION C

SUB-CRITERION C2 – FEEDING AREAS

Coastal Northern Humboldt Current is an important feeding area for eight sharks. The two most common prey species (Peruvian Anchoveta and Humboldt Squid) represent one of the most abundant marine resources worldwide as these are the most caught species (fish and invertebrate, respectively) (FAO 2022). Peru is responsible for the largest volumes captured for both species (FAO 2022). The Peruvian Anchoveta is one of the main reasons why the NHCS produces more fish per surface unit than any other marine ecosystem (Chavez et al. 2008). Within Peru, historically the largest fishery has been concentrated in northern Peru for Humboldt Squid (Csirke et al. 2018) and in northern-central Peru for Peruvian Anchoveta (Castillo et al. 2015), both located within this area. During warm periods (El Niño events or summers), these species aggregate in major upwelling centres associated with the NHCS EBSA (with traditional ecological evidence that Humboldt Squid aggregates in the central part of this area), as these centres serve as a refuge, given the persistence of upwelling in them (Bertrand et al. 2004, CBD 2017, Jian et al. 2020). Also, in the northern part of this area, one of the largest abundances of Peruvian Hake has been recorded as the fishery has developed into one of the main fisheries in Peru (Arellano & Swartzman 2010).

Results from a diet analysis of 485 Smooth Hammerheads (neonates, young-of-the-year, juveniles, and adult females) between 2013–2015, found that Humboldt Squid (27% Index of Relative Importance [IRI]) and Patagonian Squid Doryteuthis gahi (37% IRI) were the main prey (Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2017). Smooth Hammerheads presented a narrow trophic niche (i.e., highly specialised predator) in this area. In this study, 78% of stomachs contained food items and in one adult (230 cm TL) stomach, 74 pairs of squid beaks were counted (the equivalent of 74 cephalopods) (Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2017). Other diet studies of Smooth Hammerhead in the eastern Pacific Ocean (Ecuador and Baja California) indicate that this species feeds mainly on cephalopods (Bolaño 2009; Estupiñan-Montaño et al. 2009; Galvan-Magaña et al. 2013). Smooth Hammerhead has been the third most captured shark species by fisheries in Peru and the most frequently captured shark species off northern Peru between 1997–2021 (Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2016; IMARPE landings statistics). Most of the landings and fishing areas are in Piura, Lambayeque, and La Libertad (within this area). One of the most important fishing areas in Peru are around the Lobos de Tierra and Lobos de Afuera Islands, offshore of Lambayeque (Carbajal et al. 2007; Llanos et al. 2009). Thus, this area represents an important feeding ground for this species along the Eastern Pacific.

Juvenile Chilean Eagle Ray prey on teleost fishes (Peruvian Hake and Peruvian Anchoveta), crustaceans (i.e., crabs and stomatopods), gastropod molluscs, and polychaetes (Torres 1978; Castañeda 1994; Segura-Cobeña 2017). Thus, this species feeds on both pelagic and demersal prey. The most recent study sampled 77 individuals in 2015 and found 93.5% of stomachs contained food items. Prey varied according to body size, seasonality, and ENSO conditions in which the Peruvian Anchoveta represented a more important prey during warmer conditions (Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2021b).

An analysis of stomach contents from 74 Pacific Guitarfish (mostly adults) between January 2015 and August 2016, indicated that prey included coastal crustaceans (stomatopods and crabs) and teleosts (mainly Peruvian Anchoveta); diet varied according to ontogeny (Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2021a, 2021b).

An analysis of stomach contents from 44 Tope Sharks (adults and juveniles) between January 2015 and August 2016, determined that it preys mostly on teleost fishes (Peruvian Hake and Peruvian Anchoveta) and secondarily on cephalopods (Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2021a).

An analysis of stomach contents from 69 Copper Sharks (adults and juveniles) between January 2015 and August 2016, determined that it preys mostly on teleosts in which the Peruvian Anchoveta is the most important prey (43% Prey-specific Index of Relative Importance [PSIRI]). This species is considered a predator with a high degree of specialisation (Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2021a). In other places where its diet has been studied (South Africa and Argentina), its diet is composed mainly of small pelagic schooling fishes (Cliff & Dudley 1992; Lucifora et al. 2009; Smale 1991).

An analysis of stomach contents from 76 Humpback Smoothhounds (mostly adults) between January 2015 and August 2016, determined that the species preys mainly on Peruvian Anchoveta (21% PSIRI), and secondarily on crustaceans (crabs and stomatopods) and molluscs (gastropods and cephalopods) (Samame et al. 1989; Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2021a). Diet varies according to season (Samame et al. 1989).

An analysis of stomach contents from 43 Spotted Houndsharks between January 2015 and August 2016, determined that the species preys mostly on teleost fishes (e.g., Peruvian Anchoveta) and crustaceans (Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2021a).

An analysis of stomach contents from 72 Broadnose Sevengill Sharks between 2015 and 2019, determined that the species preys mostly on teleost fishes and marine mammals (sea lions and small cetaceans). This diet varies according to ontogeny with larger individuals preying less on teleosts (20% IRI) and more on marine mammals (61% IRI) (Kohatsu 2020). In other places (California, USA; South Africa; Argentina; Tasmania, Australia) where Broadnose Sevengill Shark diet has been studied, adults prey mainly on marine mammals (Ebert 2002; Lucifora et al. 2005; Barnett et al 2010; Hammerschlag et al. 2019). This area overlaps with large rookeries of South American Sea Lion Otaria flavescens located in Lobos de Tierra and Lobos de Afuera Islands, representing the main colonies of pinnipeds in northern Peru (Majluf & Trillmich 1981). This area also overlaps with an Important Marine Mammal Area which represents an ideal habitat for several marine mammals, in particular small cetaceans (i.e., Burmeister’s Porpoise Phocoena spinipinnis and Dusky Dolphin Lagenorhynchus obscurus posidonia) (IMMA 2022). Furthermore, the most important landing sites in Peru for Broadnose Sevengill Shark is adjacent to this area (i.e., Lambayeque region) (IMARPE landings statistics).

CRITERION D

SUB-CRITERION D2 – DIVERSITY

Coastal Northern Humboldt Current sustains a high diversity of Qualifying Species (17 species). This equals the regional diversity threshold (17 species) for the Central and South Pacific American region.

Pelagic Thresher, Common Thresher, Diamond Stingray, and Spinetail Devil Ray are frequently captured by small-scale fisheries operating and landing in this area (Gonzalez-Pestana et al. 2016, in Press; Alfaro-Cordova et al. 2017; Torres 2017; Gonzalez-Pestana 2022). Other species such as the Rasptail Skate is the most abundant bycatch ray species (e.g., a total of 556 individuals captured between April and July of 2009) and represents the highest catch-per-unit-effort in the trawl fishery for Peruvian Hake that operates within this area (Céspedes 2014). Large female adults of Whale Sharks aggregate along the shelf break in this area from December through March (Hearn et al. 2016, 2017; Ryan et al. 2017).

Download factsheet

SUBMIT A REQUEST

ISRA SPATIAL LAYER REQUEST

To make a request to download the ISRA Layer in either a GIS compatible Shapefile (.shp) or Google Earth compatible Keyhole Markup Language Zipped file (.kmz) please complete the following form. We will review your request and send the download details to you. We will endeavor to send you the requested files as soon as we can. However, please note that this is not an automated process, and before requests are responded to, they undergo internal review and authorization. As such, requests normally take 5–10 working days to process.

Should you have questions about the data or process, please do not hesitate to contact us.