ISRA FACTSHEETS

ISRA FACTSHEETS

ASIA REGION

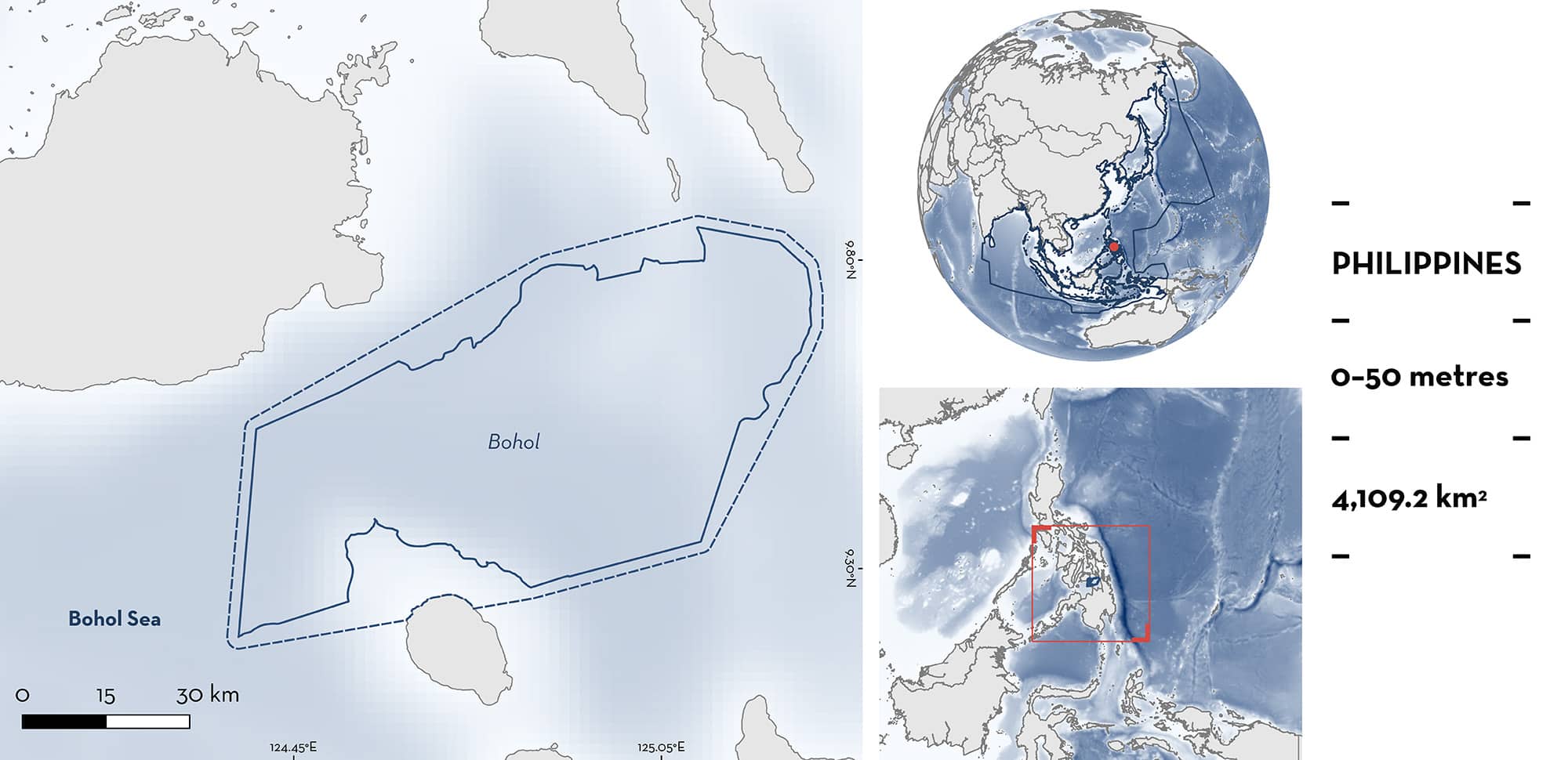

Bohol

Summary

Bohol is located in the northeastern Bohol Sea, southern Philippines. This area has a fast inflow of Pacific waters through the Surigao Strait, known as the Bohol Jet. This induces entrainment of deep, cold, nutrient-rich waters to the surface water layer. The intensification of the Bohol Jet during the northeast monsoon (November–April), combined with inflow from the Agusan River, results in high primary productivity and plankton blooms. This area partially overlaps with the Sulu-Sulawesi Marine Ecoregion Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Area. Within this area there are: threatened species (e.g., Oceanic Manta Ray Mobula birostris); reproductive areas (e.g., Bentfin Devil Ray Mobula thurstoni); and feeding areas (e.g., Sicklefin Devil Ray Mobula tarapacana).

Download factsheet

Bohol

DESCRIPTION OF HABITAT

Bohol is located in the northeastern Bohol Sea, also known as the Mindanao Sea, in southern Philippines. This area connects to the Sulu Sea in the west through the strait between Negros and Zamboanga Peninsula, to the Philippine Sea in the east through the Surigao Strait, and to the Camotes Sea through the Canigao Channel and Cebu Strait. Bohol sits over a deep basin with underlying depths to over 1,500 m that are found <9 km offshore. Sea surface currents, formation of eddies, and entrainments cause upwellings that drive seasonal variations in productivity which are also influenced by the northeast and southwest monsoons (Cabrera et al. 2011; Gordon et al. 2011). Entrainment appears to be enhanced during the northeast monsoon season (November–April) and is more pronounced in the eastern basin than the western basin (Cabrera et al. 2011).

Bohol receives waters from the large and deep Sulu Sea through the Dipolog Strait (~500 m deep) to the west, and from the deep Pacific Ocean through the shallow Surigao Strait (~60 m deep) to the east (Cabrera et al. 2011), giving rise to its unique circulation and physicochemical properties (Gordon et al. 2011). The ‘Bohol Jet’ surface current in the north of the Bohol Sea is the extension of water flowing in at high speed through the Surigao Strait (Gordon et al. 2011) and is the main oceanographic feature influencing this area. This fast inflow of Pacific waters through the Surigao Strait induces entrainment of deep, cold, nutrient-rich waters to the upper layer (Cabrera et al. 2011; Gordon et al. 2011). The intensification of the Bohol Jet during the northeast monsoon, combined with inflow from the Agusan River, results in high primary productivity and plankton blooms (Cabrera et al. 2011; Gordon et al. 2011). Bohol is mostly located over deep oceanic waters (1,000–1,500 m), although some depths are between 200 and 1,000 m.

This area partly overlaps with the Sulu-Sulawesi Marine Ecoregion Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSA; CBD 2024).

This Important Shark and Ray Area is pelagic and is delineated from surface waters (0 m) to 50 m depth based on the bathymetry of the area and the known depth range of the Qualifying Species.

CRITERION A

VULNERABILITY

Four Qualifying Species considered threatened with extinction according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species regularly occur in the area. These are the Endangered Oceanic Manta Ray (Marshall et al. 2022a), Spinetail Devil Ray (Marshall et al. 2022b), Sicklefin Devil Ray (Marshall et al. 2022c), and Bentfin Devil Ray (Marshall et al. 2022d).

CRITERION C

SUB-CRITERION C1 – REPRODUCTIVE AREAS

Bohol is an important reproductive area for two ray species.

From February to June 2015 and from November 2015 to May 2016, Oceanic Manta Rays and Bentfin Devil Rays were sampled at Bunga Mar (Jagna, Bohol Island) which represents the largest landing port in the Philippines for mobulid rays (Rambahiniarison et al. 2018). Fishing boats targeting mobulid rays travelled daily up to 60 km offshore within the Bohol Sea and fished at night using drifting gillnets set between 10 and 40 m deep (Rambahiniarison et al. 2018).

A total of 173 Oceanic Manta Rays (females = 98; males = 73; unsexed = 2) were sampled representing 11% of the total number of individuals landed (Rambahiniarison et al. 2018). Of the 63 mature females sampled, 25 were pregnant (carrying one foetus each) representing 40% of all females sampled. Near-term foetuses were recorded in February, March, and April. The size-at-birth has been estimated in this area (200–210 cm disc width [DW]) with very few studies globally that have confirmed through direct observations the presence of pregnant females and near-term embryos for this species (Marshall et al. 2008; Rambahiniarison et al. 2018; Cabanillas-Torpoco et al. 2019; Medeiros et al. 2022).

A total of 817 Bentfin Devil Rays (females = 486; males = 279; unsexed = 52) were sampled representing 54% of the total number of individuals landed (Rambahiniarison et al. 2018). Of the 235 mature females sampled, 164 animals were pregnant (except for two individuals carrying twins, the remaining animals carried one foetus each) representing 70% of all females sampled. Near-term foetuses were observed from November to June. Females at different stages of pregnancy were caught in the same net. The size-at-birth has been estimated in this area (90 cm DW) with very few studies globally that have confirmed through direct observations the presence of pregnant females and near-term embryos for this species (Notarbatolo-di-Sciara 1998; White et al. 2006; Rambahiniarison et al. 2018).

Neonates and young-of-the-year for both species have been recorded but in low numbers (Rayos et al. 2012; Rambahiniarison et al. 2018). According to fishers operating in this area, it is not common to land immature mobulids since small-sized rays are generally discarded at sea when caught in their nets (Rayos et al. 2012). Therefore, these life-stages might be more abundant than observed at the landing site.

CRITERION C

SUB-CRITERION C2 – FEEDING AREAS

Bohol is an important feeding area for four ray species.

Oceanic Manta Rays, Bentfin Devil Rays, Spinetail Devil Rays, and Sicklefin Devil Rays aggregate seasonally in this area (November–May) to mainly feed on euphausiid krill (Rohner et al. 2017; Stewart et al. 2017; Masangcay et al. 2018; Bessey et al. 2019). The fishing season for mobulids in this area coincides with the northeast monsoon when increased upwelling leads to higher primary productivity in surface waters (Cabrera et al. 2011; Gordon et al. 2011). Fishers catch mobulid rays using drifting gillnets between 10 and 40 m deep, and whenever krill is present because mobulids spend a considerable amount of time at the surface to feed (Acebes & Tull 2016). All four species of mobulids are caught together, sometimes in the same net (Rohner et al. 2017). Between 2013 and 2014, 25% of 790 recorded fishing trips captured more than one species of mobulid in a single net (J Rambahiniarison unpubl. data 2017).

From November to May 2013–2015, the stomach contents of 89 mobulid rays were evaluated from individuals landed in Jagna, Bohol Island, each of which were caught in this area (Rohner et al. 2017). The euphausiid Euphausia diomedeae was the major prey item for all mobulid species, recorded in 91% of all total stomachs. A strong dietary overlap was found in all mobulid species which suggests that in the Bohol Sea during November–May euphausiid krill are an abundant resource (Rohner et al. 2017; Bessey et al. 2019). This krill has a large size (10–15 mm) compared to other zooplankton and has a swarming behavior that makes them a high-value prey source for large filter feeders (Rohner et al. 2017).

From January to May 2016, the diet of Spinetail Devil Ray was evaluated using 16 stomach contents and stable isotope analyses (Masangcay et al. 2018). Spinetail Devil Rays fed predominantly on the euphausiid Pseudeuphausia latifrons. Larger females of this euphausiid were the most dominant in the diet of Spinetail Devil Ray, which coincided with the peak of the reproductive cycle of the krill (Masangcay et al. 2018).

From December 2012 through to May 2014, muscle samples were collected from Oceanic Manta Rays (n = 42), Spinetail Devil Rays (n = 42), Sicklefin Devil Rays (n = 35), and Bentfin Devil Rays (n = 73) at a landing site in Jagna, to study their feeding ecology using stable isotope analyses (Stewart et al. 2017). The diets of the four mobulid species largely overlapped with an intake dominated by zooplankton. Trophic niche overlap in mobulid rays increases as resources become scarcer, such as in the Philippines oligotrophic tropical waters (Stewart et al. 2017). This could increase the reliance of large filter feeders on high-biomass prey patches that are sparsely distributed (Rohner et al. 2015; Armstrong et al. 2016). Mobulids appear to require prey densities that exceed a threshold level to make feeding energetically profitable (Armstrong et al. 2016). Consequently, in nutrient-poor regions, there may be fewer prey patches of adequate density, resulting in multiple sympatric species converging on the same high-density prey sources with greater trophic overlap (Stewart et al. 2017). Thus, this highly productive area within an oligotrophic region represents an important feeding area for an assemblage of mobulid species.

Download factsheet

SUBMIT A REQUEST

ISRA SPATIAL LAYER REQUEST

To make a request to download the ISRA Layer in either a GIS compatible Shapefile (.shp) or Google Earth compatible Keyhole Markup Language Zipped file (.kmz) please complete the following form. We will review your request and send the download details to you. We will endeavor to send you the requested files as soon as we can. However, please note that this is not an automated process, and before requests are responded to, they undergo internal review and authorization. As such, requests normally take 5–10 working days to process.

Should you have questions about the data or process, please do not hesitate to contact us.